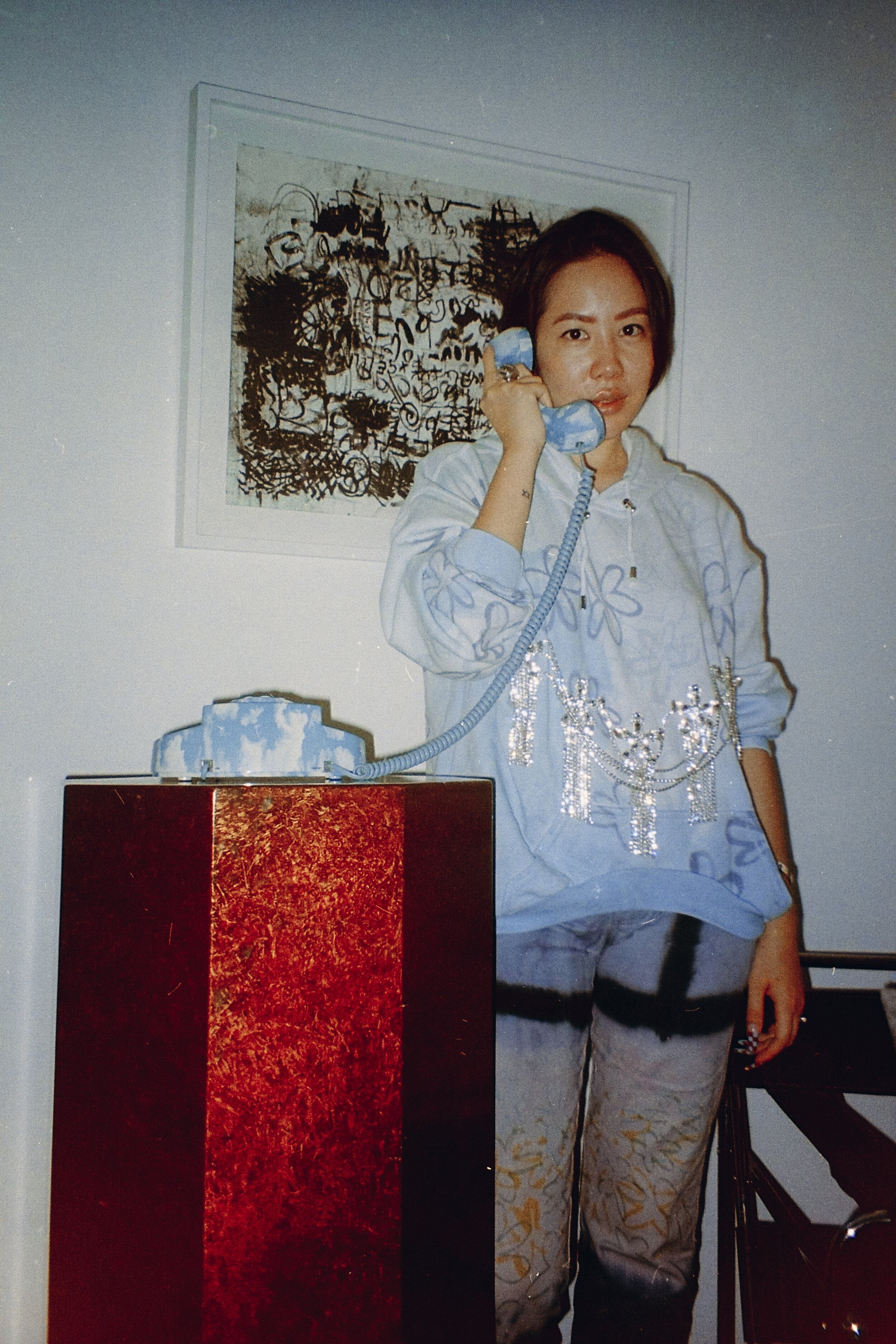

Some remember Fashion's Night Out with a twinkle in their eye, the tents at Bryant Park are a thing of the past, and fashion has instead sauntered downtown. Is nostalgia on the list? Heritage logos and saddle bags have been traded for pool-blue Telfar shoppers and backless Kim Shui qi pao’s as PR maven Gia Kuan moves steadily through the second year of running her namesake consultancy. Following years at Comme des Garçons and Nadine Johnson, Kuan now represents some of the most exciting names in NYC Fashion, Arts, and Culture today. These "clients" are more likely to call her a friend than their PR agent; the relationships she has with those she represents extends far beyond the scope of traditional PR campaigns and influencer lists. The difference in Kuan's consultancy is that she is part of the community whose voices she helps to amplify and shape. An immigrant who moved to New York with a dream, Kuan worked three jobs during school. With no friendly, phoned-in favors from daddy to get her in the door, she’s never had to ask, "what's authentic?" She doesn’t have to try to understand, she empathizes. Her intuition is a skill that she has sharpened through sustained self-awareness, and it guides her as she actively redefines her entire profession. Kuan builds bridges between curation, marketing, and public relations in today’s distorted landscape so that brands may see themselves reflected in the decisions they make and the legacies they leave.

STP's Lindsey Okubo sits down with Kuan to talk about life in the fast lane, the cracks in the system, and the realities of an industry that has us all wide-eyed, inspired, and anxious.

Lindsey Okubo: You started your own consulting agency just over a year ago and represent some of downtown’s biggest names in fashion including Telfar, Area, PriscaVERA, Kim Shui, Lou Dallas, Puppets and Puppets and Barragán. Can you give us the lowdown on your trajectory, from being Arts and Culture Director at Nadine Johnson and cutting your chops in the early days at Comme des Garçons and Dover Street Market?

Gia Kuan: I had just moved to New York in 2010 with no professional fashion training. I graduated school in Australia with a degree in Communications and Art History, but at one point, was pursuing a degree in Law [laughs]. I wanted to be a food editor or work in fashion. I applied for so many internships and no one was replying to me. They only ever looked for one intern, and it had to be someone they knew. I decided to take a break from Australia and come to New York for post-grad; a fast course at Parsons in Fashion Marketing. My rounds of internships secured me my first job at Comme des Garcons. I was there for a good five years working under the Press Department. I also worked on the Dover Street Market press when it opened in New York in 2013, and was part of creating and witnessing that culture at the beginning. Looking back, I still haven’t seen anything like it, the way that the staff was curated alongside the work culture behind it.

After five years, I took a turn and went into agency mode with Nadine Johnson. I headed her Arts and Culture department. There, I did press and communication strategies. Nadine was such an icon, since the late 90s she was known for throwing the best parties in town –– a straight from Sex and The City Samantha inspiration. She kind of just threw me into fire, which built my confidence. Even when I told Nadine that I didn’t have completely linear experience, she said, "don't doubt yourself, just do it." That mentality is so much of what I believe in now. If you have a sense of “this might be something,” don't overthink it, do it.

LO: It seems like embracing that mentality is what allowed you to go off and do your own thing, right? That, and wanting to help build the community that you were a part of and to see it thrive.

GK: While at Nadine, I delved into the brands I loved, which at the time were very much the new, young, rising talents in New York City. I moved to New York during a period in which fashion wasn’t as raw. It was Bryant Park, it was Fashion’s Night Out, and it didn’t get brought downtown. My first client was Eric Schlosberg, who worked with me at Dover Street, followed by Robert Childs, who at the time was launching his menswear brand, Childs. I realized that a lot of the young designers were usually one or two people shows. If I liked the collection, I’d want to push them forward even if there was no monetary return initially. I would rather see the market change to reflect what I like, and what I know a lot of people like me like.

LO: What does that change look like?

GK: It tells a deeper cultural narrative. Fashion before then was very white. Hood By Air was one of the early pioneers of this new fashion vanguard per se, and Telfar had always existed but it wasn't on the calendar. The question became: how do I bring that narrative up a level to reach everyone who just doesn’t know about it yet? There is a hierarchy in place and this system doesn’t always allow smaller brands to push further. Without being totally conscious of it, I was also vouching for a lot of minority brands because I wanted to tell a multidimensional story and show that clothing didn’t have to look a certain way. Brands like Lou Dallas, who I worked with, brought something more fantastical that makes us question if fashion needs to be the clothes that we wear to work. It’s about changing those rules.

LO: What is fashion there for? As we’re thinking about changing narratives, what really is the importance of words like “heritage” and “legacy”?

GK: Fashion means so many things. It's a way of personal expression. Depending on what you wear, it goes beyond function. If you think about brands like Telfar, the designs are fantastic but there's something more deeply rooted there; what you're supporting is a cultural community that you want to be a part of. It’s the same with Kim Shui and the hypersexuality and confidence that she puts into the Kim Shui girls, you want to be part of it. What fashion means to me is asking, how do you support that community? How do you extend your personal narrative through mixing and matching these subcultures as wearable items into one?

LO: Now things feel more like they're in visual communication through the choices that the consumer makes. I think a lot of designers have felt this weird sense of competition between each other and I feel that's something you’re changing through this community downtown. All these disparate voices have become crucial pieces to the collective framework.

GK: I came to New York with the American dream in that I wanted to be part of this industry, but quickly felt disillusioned by it. (The Industry) becomes something other than how you've envisioned it, but that magic is still there. How do you make that happen or bring it back? It stems from the work environment; the way that the community interacts with each other. All of those stereotypes that you see in fashion, they definitely used to exist. In the mid-2010s, this slightly different generation of kids came up on the scene. They were very crafty, very DIY before it became such a phenomenon. They were breaking the rules of what wearable art could be, they were more supportive of each other because they went to school with each other, or interned together. That dialogue was important. At the end of the day, are the people in positions of power really the ones deciding what should? We have come to realize that you don't have to show within the context of a certain time or place, you don’t have to follow a certain format. I said this three or four years ago and I'm saying it now, they don't have the power, you do. If all of the designers came together and said, we're not going to do this, that's the only way that this system will crumble.

LO: What do you think is the hesitation for people? It sounds so simple when you put it that way, but there is this underlying sense of fear because of firmly rooted ideals of what success looks like based on validation from the old guard.

GK: There's some truth to the idea of passing knowledge down through generations, but it has also created problems. Young designers are paired with heritage designers, and while these are very lucrative companies, they’re not always thinking about these young brands; who they really are, who they speak to. They're not born out of the same time, they're not functioning the same way. I think that it's important to have that mentorship program be more balanced. A lot of young designers do feel daunted being told by a legacy designer of 30 years that you're not going to succeed unless you do x, y, z.

LO: Right, and thinking about the ways success can be subjective but at the end of the day, fashion is still a business. Questions of where you are stocked and what your sell-through is are still valid.

GK: Exactly, even the wholesalers can be bullies to these younger brands by trapping them for seasons at a time so they can have the exclusive buy. Sometimes young brands don't know any better. Before it was like, “oh my god, I really want to be at Barney's!” but look what happened to Barney's. We've seen that in a lot of multi-brand retailers because certain formats aren't working anymore. It’s an exciting time for brands because if you can do things direct to consumer, you can have 100% control over your distribution, your voice, and your own time.

LO: Right, and if that’s the case, their exposure would come from magazines or the press. Many of these publications, historically speaking, used to have distinct communities behind them. That’s shifted. The brands are the ones with the communities now, with key people behind them who represent the values and a multidimensional demographic. What happened to publications?

GK: It's a double whammy and a good question because it's also a very sensitive time. We know Conde Nast has their own set of problems, but from the devil's advocate side, those “problems” existed because they represented a certain voice, perspective or demographic. It's really important to have diversity across the board. At the same time, if you apply the same diversity rules to every single publication, then everyone is advocating for exactly the same thing. This year when a lot of people were canceled for various reasons, they often had small teams and a distinct voice that appealed to a certain audience. There’s something about that cancel culture which I don’t fully agree with, because then you’re just removing certain perspectives from the conversation. It's like someone coming to me at GK Consulting where I have, like, two employees and being like, you have no diversity in your staff. I wouldn’t know what to say, I too had a specific vision as like a minority Asian woman. The applicants who apply to my business are also probably drawn to me because they share the same narrative.

LO: Yeah, and with cancel culture, to what extent are you allowed to have diversity in opinion? To what extent do you have to police yourself to make sure to cater to other people's opinions, and where do you draw the line with that?

GK: It's very tricky. I've been thinking about this all year. I don't know if I'm just being the devil's advocate because I don't agree with all of the times publishers and magazines face backlash because of what they say. What happened to independent journalism and free speech, you know? It’s more about accountability, not cancelling each other.

LO: I feel like everyone is kind of a weird clone of someone else. We’re all expected to have the same affinities, references, interest in food, love for this brand, whatever it is. Individuality is now a trend. You can’t really be in your own lane without feeling like you have to also be up on the latest news.

What resources, conversations, etc. are you using to shape your vision?

GK: Honestly, this is probably bad for me to say, but I really don't read fashion digests. My staff sends out daily news updates and I read about it when there’s something that I need to know. I feel like too much competitor research might deter me from what my vision is.

I actually read a lot about food. A lot of it also comes from my daily conversations. I don't know if I ever really sit down and strategize what I envision for Gia Kuan Consulting, I feel like I've just been doing it. It's just as simple as how to help the brand get their voice to the people in ways that are not so straightforward. Previously, I think that wasn't really even in the scope of public relations because people think that the publicist is doing a very certain, traditional scope of service.There are so many other ways to raise visibility for your client’s brand. A lot of it now is just being culturally attuned, being a matchmaker of sorts. It's saying, ‘oh, I think that person will think it's cool, let me connect you with them’ because you never know what that person can bring you.

LO: Your clients are diverse and require this balance between curation, marketing and PR. All of these words have seemingly meshed into one sticky existence now, how do they all still differ and do they need to differ?

GK: There's definitely a little bit more of a blurred line now, more so now than ever. The textbook definition of what PR is that you are engaging with the public to raise the profile of your client or help them gain visibility in a positive way. That is still really what I do, being the bridge between the direct consumer and the media. How you build that bridge is now very, very different. The scope is now more fluid. We’re working with not only the external public, but oftentimes with how brands talk to their audiences directly. In the past, you usually had a third party that helped do that for you. I’ve also been helping brands consider conversations in how they should speak to their staff. Everything has to be in sync now more than ever. What happens internally can very quickly be externalized.

LO: Fashion is traditionally plagued by this idea of relevancy. How do you best ensure that working in this industry is sustainable?

GK: Yeah, for sure. That's why we’ve seen the rise and fall of a lot of these young designers. It's a pretty brutal industry. I've worked with brands who are now no longer brands but during their time were amazing. I left fashion at one point to go to Nadine's and now I'm back, but I don't read fashion news religiously. I think if you keep your life fashion and fashion only, then it can become a little disillusioned. Fashion is never just clothes, it's always borrowed from something else. You can't live and breathe fashion alone. Everything is intermixed.

Edited by Lauryn-Ashley Vandyke